It has taken me decades to understand more fully and define what I have always been, a formalist. In August of 1975 I emerged into the London art scene to teach in the Fine Art program at Fanshawe College not as an image-based artist dealing with the prevalent regionalist approach to my studio activity but rather as an abstract artist. London was very much, at the time, the bastion of image-based work both historical as in the work of Paul Peel or in a more contemporary way like the works of Jack Chambers and Greg Curnoe who championed Regionalism.

When Wyn Geleynse asked what my work was about in 1977, on a studio visit to do some welding for him, I told Wyn that I was a formalist. At the time, I could not articulate my stance in any great length much beyond stating my position as a visual artist. What I was not about was representing things or experiences from everyday life be it the figure, the landscape or any aspects referencing London, Ontario. As a result, the local artists could not count on me to be a Regionalist. That put me on the outs with some of London’s visual artists who were still very much immersed in that way of thinking and working.

What interested me were ideas that grew out of my imagination that did not have a precedence in that the image I was working on had not already been made before as I had developed it.

Repeating something that others had already made was of no interest to me. What was of interest to me was working within the abstract tradition though my own eyes. Specifically for a time, the geometric tradition that focused on, line, form and movement.

The work over the decades has evolved slowly but surely. Olga Korper, on one of her studio visits asked me, “where are you going with this work”? My reply, for which I do not think Olga wanted to hear, was, “I let the work inform me’. The work that has just been constructed offers options to follow that may or may not lead to the next body of work.

As Alberto Giacometti stated “It is all about trying. The rest will follow in place”. Falling into place may take years to unfold fully. Better to have tried than not to have taken the risk of pursuing what was hinted at.

Time has a wonderful way of revealing paths to pursue. It also clarifies those decisions made along the way to where one is in one’s thinking and refreshes one’s memory to where one has been.

When I decided to abandon my initial training in chemical technology to return to school and study fine art in September of 1978, I found myself in the throes of Formalism spearheaded by Clement Greenberg. The formalist art that inspired me the most was that of the American sculptor David Smith. Who himself had been influenced not only by Russian Constructivism but also by the work of Pablo Picasso and Julio Gonzalez. Once I discovered these important historical figures, I found myself pursuing formal work that grew out of the Constructive tradition. It was not modeling or carving that held my attention but rather the additive approach using welding as a means to construct an image.

Very quickly I found myself interested in the geometric tradition as an approach to constructing a final image both two-dimensionally and three-dimensionally. Once I decided that sculpture and painting could provide me with a fresh way of looking at art, that did not need to have a social narrative attached to the final outcome, I was on my way to defining who I would be as a visual artist.

Welding as a process to construct my work continued throughout my two years at Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida. With the completion of my MFA in 1974 came a year of reflecting and examining other ways of forming my work. While exploring those other ways of thinking, I set up a number of linear metal sculptures, in my Windsor, Burrough’s Building, studio with the aluminum I had returned to Windsor with. It was not long before I understood that the constructive approach to image making was what would drive me forward with my studio activity.

At this time, I did not see myself as a Formalist but rather as someone working with regular and irregular forms to construct my ideas. My early welded sculptures made use of closed box forms that were influenced by David Smith to work with linear components to define a final image. In 1974-1975 I explored flat planes to create movement and get the viewer to move around the sculptures. That interest in flat and curvilinear planes continued through 1976 to 1978 ending with the welded steel “Intra-Structure”, “Platform”, and “Axis” series.

Colour, early on, was an important component to my work that was influenced by my interest in painting. That interest in chromatic colours came to an end with my sculptures early in 1976 when I decided that I would follow a truth to materials dictum and abandon colour as I felt, at the time, that colour imposed itself on form and frequently diminished the structure.

For me it was all about the form and not about the emotional value that colour brought on. For me, the Canadian sculptor Robert Murray was one of the few sculptors whose sculptures were not diminished partly because of his use of dark strong colours.

My interest in line and the geometric continued with the “Table as Image as Structure” series that took me from 1979 into 1987 when I decided to put abstraction aside as I had been exploring it to examine image based narrative work as in the large outdoor installation titled, “Images”, May-June 1987. That way of exploring three-dimensional imagery continued until 2010. Even during those years, I approached my work from a Formalist perspective. From the point of view that I reduced my imagery down to their bare essence in keeping with Constantine Brancusi’s approach to abstraction. The origins of the images were always apparent from my reductive portrait in profile to the Billie series in which Billie’s portrait was only hinted at. I was not interested in a traditional perceptual portrait but rather in a formal conceptual approach to her portrait.

Texture is an important component of Formalism. The nine, 4’h x 4’w x 2”d panels of Billie were defined by texture using sintered steel and fiberglass resin that were laid over a variety of materials that had initially been covered with fiberglass resin. In the end, they created a new and fresh way of looking at my portraits of Billie.

Even the series dealing with anger and rage as a topic, as was the previous series “Portrait of the Artist” were brought together in a very reductive manner. Repetition of elements was key to defining the final image.

Though the portraits of Jeff Sproul and Megan Spencer were perceptually correct, how they were brought together was in a formal way repeating pattern and linear elements combined with one form of texture or another to pull the composition together.

The final image based narrative work ended with the “Icarus” series from 2005 to 2010. Only four stylized images that formed the “Icarus” series were used to complete the narrative about taking risks in life. The Greek myth of Icarus was the springboard for the final approach to working with images in line with the formal tradition. The “Icarus” series marked the advent of my third distinctive way of working in the studio when I decided to re-examine abstraction in 2011 after a year of reflection to determine where to take my studio activity next.

This third phase in my studio work marked a move away from freestanding sculptures to those taking advantage of the wall as a support structure. This move changed how the audiences would view my three-dimensional work. Though some of my earlier sculptures, prior to 2011, as in the “Portrait of the Artist”, the “Billie” and “Icarus” series did make some use of the wall most of the sculptures produced were free standing asking the viewer to experience the work by either walking around the sculptures or through the work. The sculpture as a result was understood by looking at it from an oblique. My return to wall dependent sculptures asked the viewer to examine the work perpendicularly, much like in viewing a drawing or a painting.

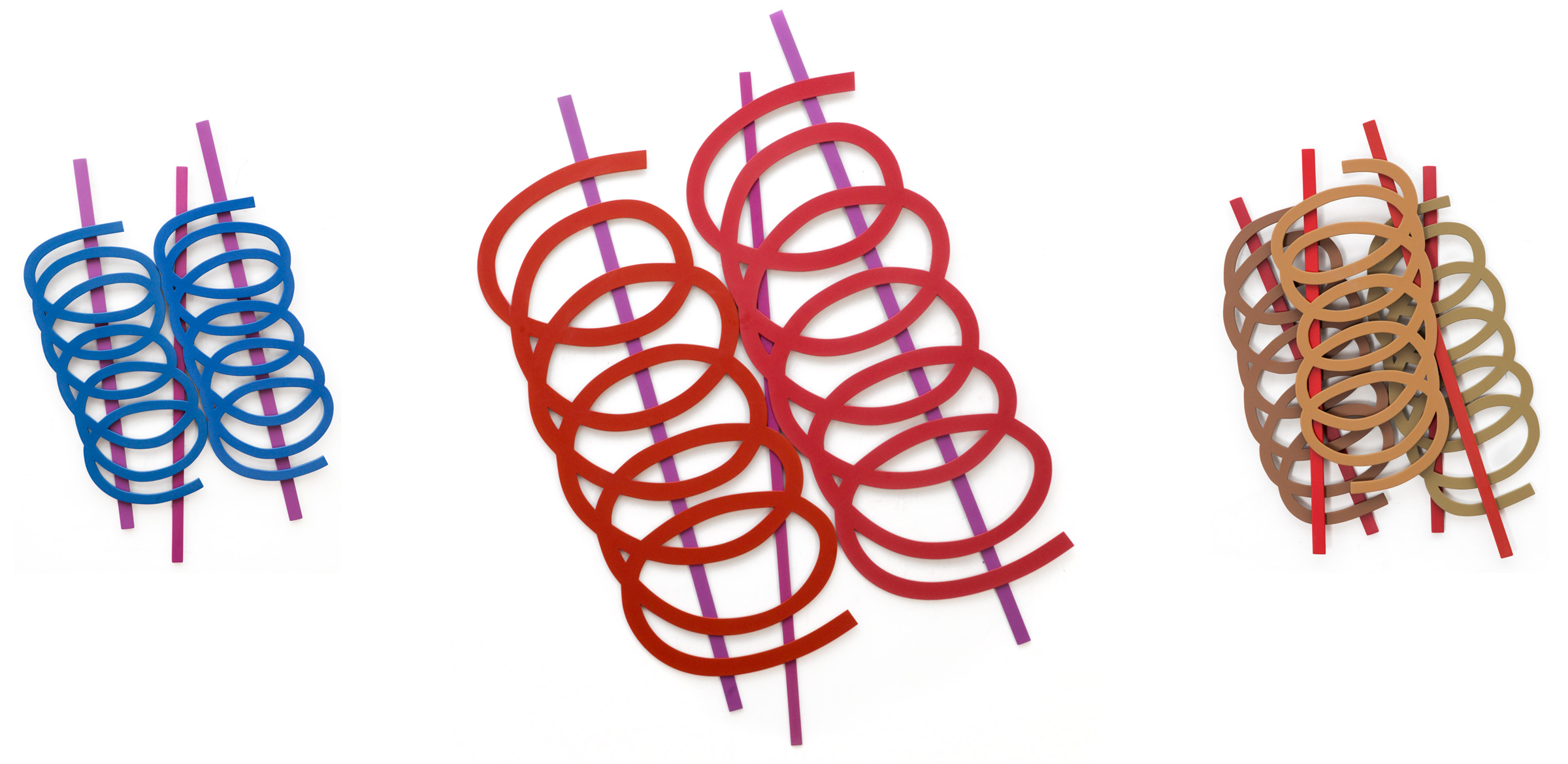

The “Icarus” series came to an end in 2010 and ushered in a new use of materials and processes used to define the final formal compositions. Line, texture and form were combined to bring my three -dimensional work together. Repeated pattern and texture added to the visual experience for the viewer. The viewer was not given a historical narrative to dwell on or given some social context to relate to. The work exists only on its own terms. What you see is what you get that James Mc Neil Whistler propounded, late in the 19th century. The grid was re- introduced as an organizing tool. The grid has been used in a variety of ways. At one point the grid became the subject as in “Crosscurrent No.8” January 2017. The grid was defined by a repeated pattern as in Avanti: Circle Series No.13” April 2011 or as a linear structure as in “Crosscurrent No.7” January 2017.

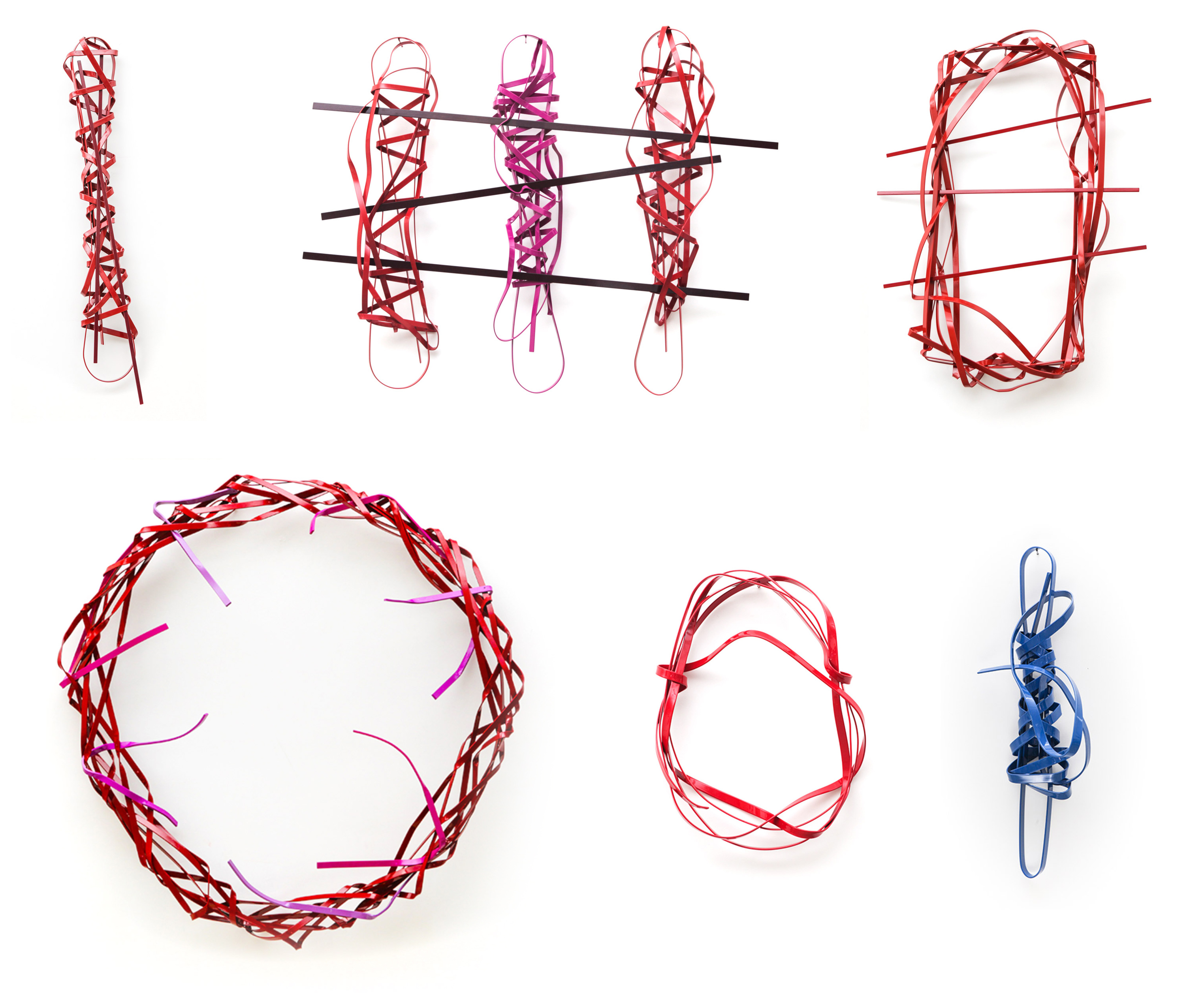

The re-examination of strong colours to define my sculptures came after working with tin and copper over a five-year period between 2011 and 2016. The tonal colours that emerged with the copper and tin sculptures, through the use of liquid patinas, developed into a return of the use of strong chromatic colours that began with the “Wrap” series, that followed the “Avanti” and early “Linear Composition” series, and continued throughout 2016. Colour in the early “Wrap” sculptures, starting with “Wrap No.1” April 2016, was restricted to one colour. In time, as the series developed, so did the number of interacting colours that were brought together to visually expand and complete the composition as in “Wrap No.12” August 2016. The formalist use of colour re-emerged with a vengeance as I continued to develop and construct the “Wrap” series. The lyrical, twisting lines of the “Wrap series became the primary subject of this body of work that was enhanced by the further addition of strong chromatic colours.

The linear elements of the “Wrap” series now physically reached out into the audience’s space only to eventually return to their beginnings. The linear elements, at times, compressed the overall form to create a tightly packed core or focused on the perimeters leaving an open core.

Strong chromatic colours at times visually expanded the form. At other times the chosen colours compressed the continuous lines moving from an open to a tightly packed number of lines.

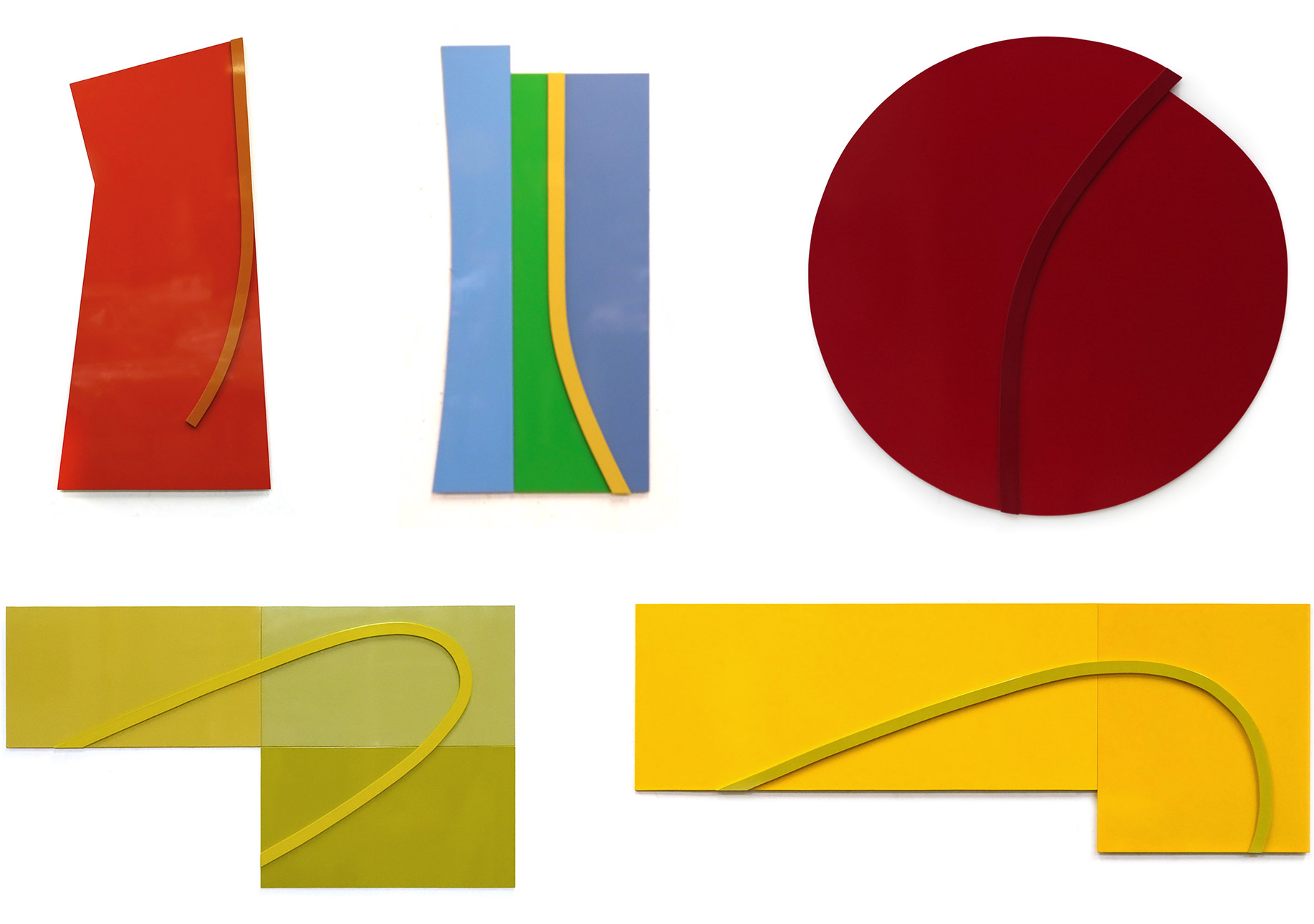

The flat linear components that preceded this series were tight to their larger surface whether as in “Linear composition No.1” August 2011 or “Zig No.2” September 2015. That approach to the use of line continued in the “Journey” and in the subsequent series of sculptures that followed the “Wrap” series.

“Crossings No.13” February-March 2017, which was defined by the cross movement of three curvilinear lines across two separated, irregular shaped grounds ushered in the “Journey” series in which only a single line moved across one large open field. Once again, strong chromatic colours were chosen to heighten the tension between the singular line and the large open field. Where the “Journey” series focused on combining a few colours to hold the composition together, the “Nazca”, “Inca” and “Above and Over” series greatly expanded the number of colours that supported the composition. All three of those series made use of curvilinear elements that were articulated by the carefully chosen colours and, in the end, held the composition together.

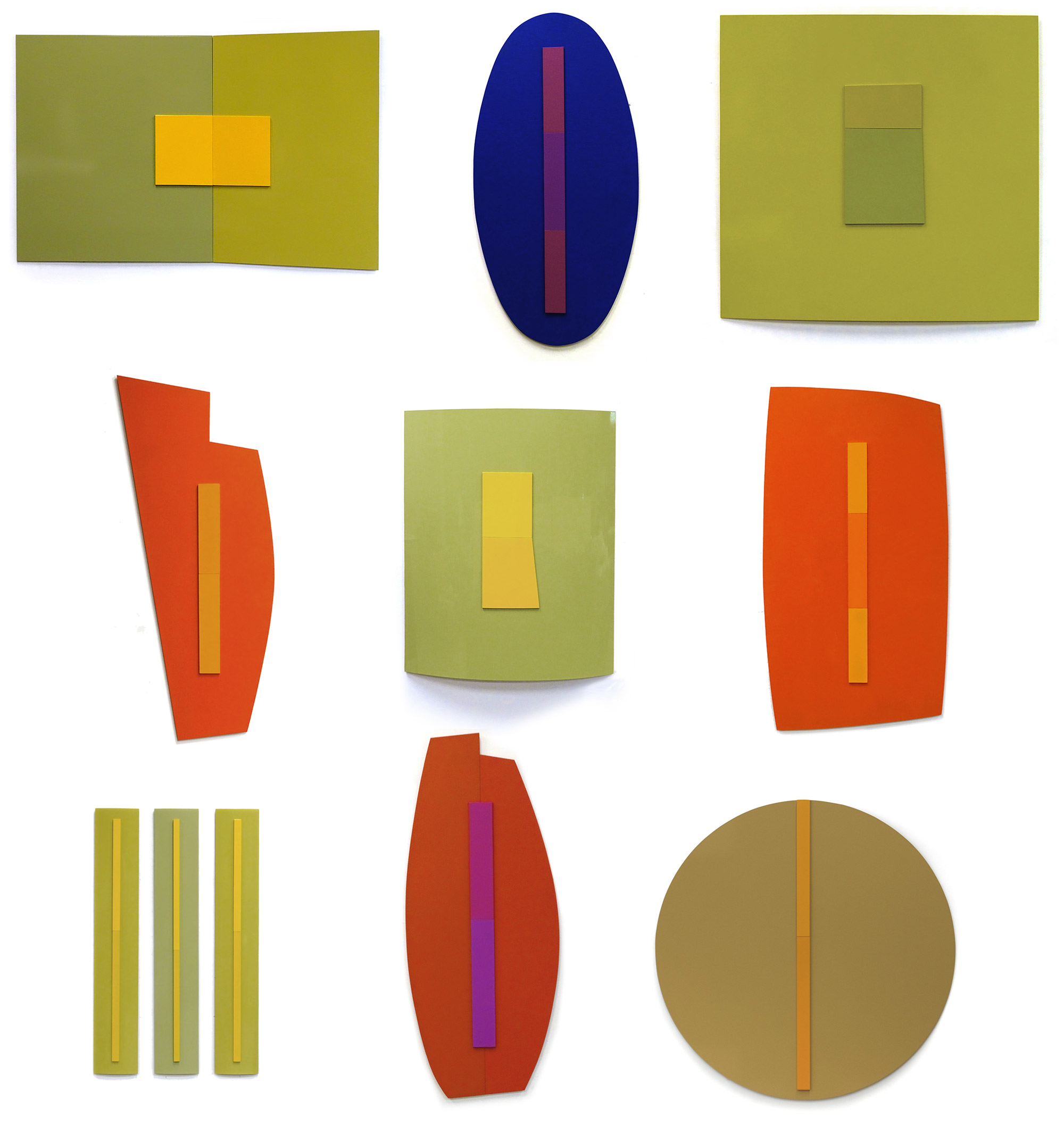

The “Fusion” series represents another example of a body of work that has evolved out of a previous series. In this case, the “Fusion” wall sculptures grew on the back of the “Journey” series in which a single line was situated over a large open ground/field. The singular line has now expanded to include several shapes by butting each other, edge to edge, to produce a more complex shape holding the centre of the overall composition, much like in the “Journey” series. This process has allowed the addition of more colours to be added to create an even greater complex, chromatic composition.

Form is an important component in Formalism. The larger grounds of the “Journey” series initially examined irregular shapes that formed the grounds. In time, there was a return to traditional geometric ground for the linear elements to interact with.

The “Crossings” series with its multiple linear elements continued to explore the simple dynamic relationship between line and plane. Colour in the wall dependent sculptures became more complex as many colours now interacted with each other to bring the composition together. In time, the large open planes became the dominant element with the line or lines acting as support for the conclusion of the compositions.

With the “Inca” and the “Above and Over “series line acted as a foil to create movement while the irregular grounds created a dynamic alternative to the more geometric grounds found in the “Crossings” series.

With the advent of the “Nazca” series came a shift in the number of linear elements that were brought together to construct the final sculpture. Line suddenly filled the ground. Once again, a number of different chromatic colours were brought together to bind the composition. The number of grounds used to construct the image were multiplied. Unlike the “Inca” series the different grounds now touch, forming a complex collection of grounds for the linear components to move across. The lyrical lines of the “Inca” and “Above and over” series now became aggressive as in “Nazca No.5” March 2019. Once again it was the line that held the chromatic compositions together.

Over the decades I have revisited a number of series. One of them was “Crossings No.4” 2013. I will do so if I can rework a composition in a new and fresh way. In 2013, the material was copper and tin with tonal colours derived from liquid patinas applied to the surfaces. In 2022, “Crossings No.4, variation No.6” May-July 2023 was constructed using aluminum with strong chromatic colours. Colours were now achieved using the industrial powder coating process. Colour was, once again, very strong as in the “Wrap” series from 2016.

The renewed interest in composition “Crossings No.4”, 2013 continued, the placement of a straight linear component to hold the center of the composition while the lyrical lines moved outward towards the four edges.

The follow up series titled, “Crossings Unfolding” took the vertical composition of the updated “Crossing No.4, Variation No.9” March-April 2024 and made it a horizontal one. The singular straight vertical line was now replaced by several vertical lines and as the series continued, at times, of varying widths and heights. The horizontal arrangement enabled a greater number of colours to interact creating a greater visual chromatic experience. The variety of straight linear elements add not only a visual tension but also creates a sense of movement. The newest body of work falls strongly within the framework of Chromatic Formalism.

A kaleidoscope of colours defines both “Crossings Unfolding No.2 and No.3”. There is a complexity of subtle layered space that is orchestrated in “Crossings Unfolding No.3”. Chromatic Formalism is re-enforced and expanded with the addition of the grid structure that visually knits and holds “Crossings Unfolding No.4” together. “Crossings Unfolding No.4” as a composition is reinforced even further with the greatly increased number and variety of interacting colours.

Formalism is the product of pure imagination that is not born out of some social context/ content based on the reproduction of imagery and experiences from daily life, instead valuing form over narrative.

The grid is formed by a set of nine repeated double looped lyrical lines individually attached to a square unit that connect to form three horizontal bands that move from left to right. A further change to the series occurs with the introduction of three repeated different coloured grounds. The changing short and straight linear elements differ in colour from square to square building on the varied chromatic composition.

A different strategy was presented with “Crossings Unfolding No. 6”, January-February 2025. This time offering alternating different full coloured horizontal bands, to form a three-band composition. The unfolding horizonal, double loops, once again, continue to move uninterrupted across the three coloured grounds. The unfolding lyrical line, with this sculpture, has now returned to being one colour as it marches across the picture plane.

The next development in the “Crossings” series, "Crossings Rising", made a radical departure from the wall sculptures begun with “Crossings No. 13” from 2017 and the subsequent sculptures that have emerged since then. For the first time, since the “Wrap” series of 2016, the ground supporting the linear elements has been eliminated. The linear elements of the new series are now attached directly to the wall surface much like the earlier “Wrap” series were.

Where the linear elements of the “Wrap” series moved in and out of the viewers physical space the new series has the linear elements flatly hugging the wall forming, in its organization, an expanding composition.

In spite of my shifts over the years, I have never fully abandoned my formalist roots and ways of constructing my work. Rather, I ultimately expanded on how line, form and colour came together.