I have been making working drawings as proposals for sculptures from the time I was a fine art student at the University of Windsor. I also made works on paper and on small pieces of canvas as studies for the paintings that I was working on during that period. Those drawings as ideas continued throughout my two years as a graduate student at Florida State University.

.jpg)

The works on paper became a tool for exploration that in the end foreshadowed the innovations to come. They also pointed to other ways of examining a composition that revealed another dimension to my studio activity.

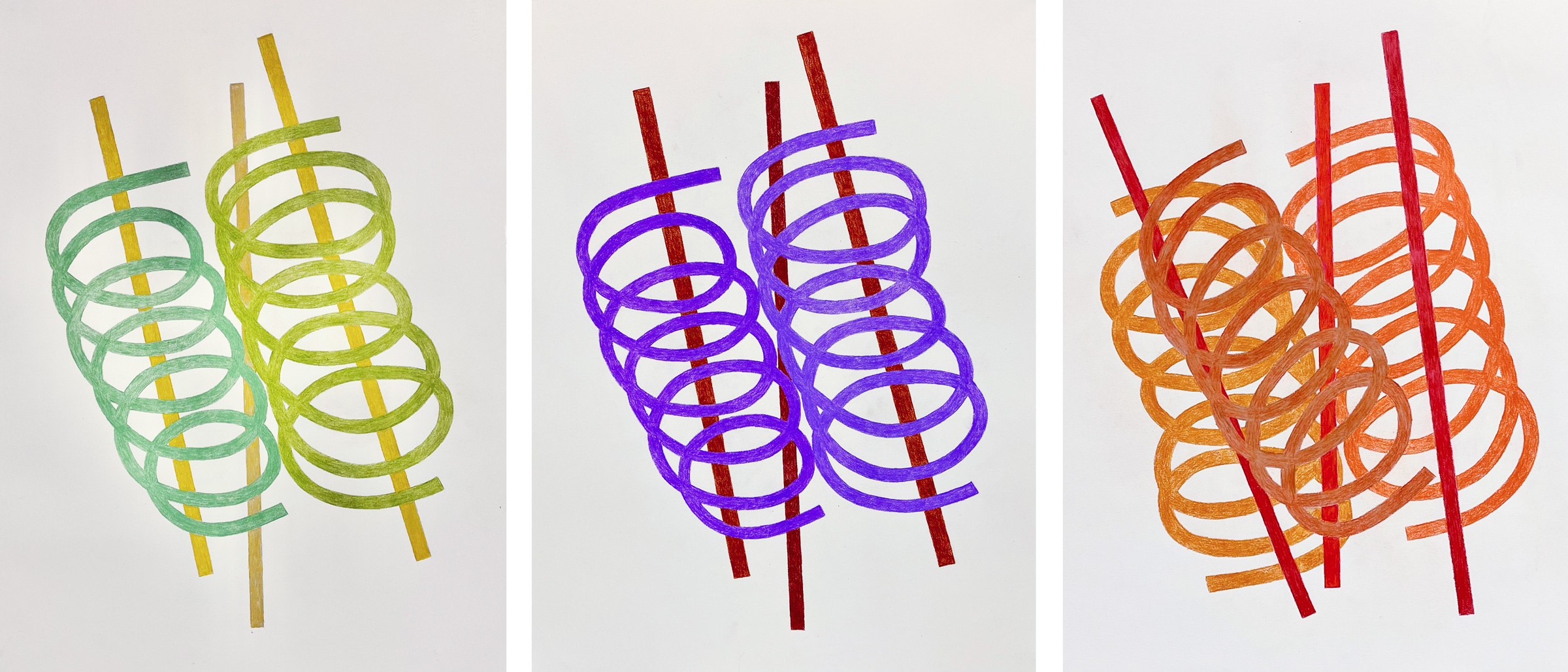

Drawing as a process and way of working to record my thoughts has had different levels of involvement that was frequently determined and fed by what I was working on in the studio at the time. The different approaches to the final image varied as did their finish. I have worked with a variety of styles materials and techniques from coloured pencils to crayons to charcoal and graphite as well as pastel powder. Over time, my approach to drawing has changed and evolved along with my sculptures. The way I chose to develop my drawings was determined by the sculptures I was working on at the time as each of my distinct three working periods asked something different of me. Over the years, I have continued to explore many different ways of completing the drawings as I have also done with my sculptures.

A great deal of my drawings over the decades have been notational in nature. For me, the idea drawings have been primarily a record of my thoughts and a possible directive to the making of my sculptures. There have been times when no drawings existed prior to making a model of a proposed sculpture. There have been times when the drawings have been developed from a model and at times from the finished sculpture. There is no order that to which I adhere. Whatever the moment dictates, determines whether the sculpture develops due to a drawing or due to a model.

During 1977-1978, I did many streams of consciousness drawings as ideas for welded steel sculptures. I would make one drawing after another until I felt I had reached my limit during that sitting. They were then placed in envelopes that were dated and set aside. That process continued until the envelope was full. Sometimes weeks or months would pass by before I looked at what I had laid down on paper.

Over the years, I have made three different kinds of drawings. The first kind were my idea sketches that were made primarily for me. When finished they were dated and stored away to be looked at another day. Some days produced many that were always dated before going into envelopes. When I decided to look at them again after days, weeks, or months, I knew which idea came first. With the passing of time, I could see those ideas that I had laid down with fresh eyes as I had moved on.

The second kind of drawings were finished works on paper that may or may not ever be exhibited. These were made before the sculptures were realized. However, the images of the potential sculptures from this second grouping may or may never be constructed. The drawings, however, remain a record of my thinking and activity.

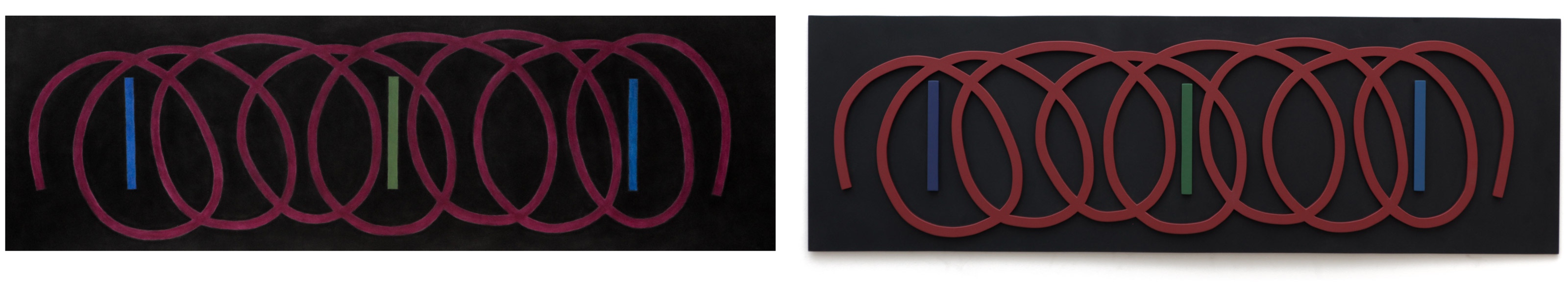

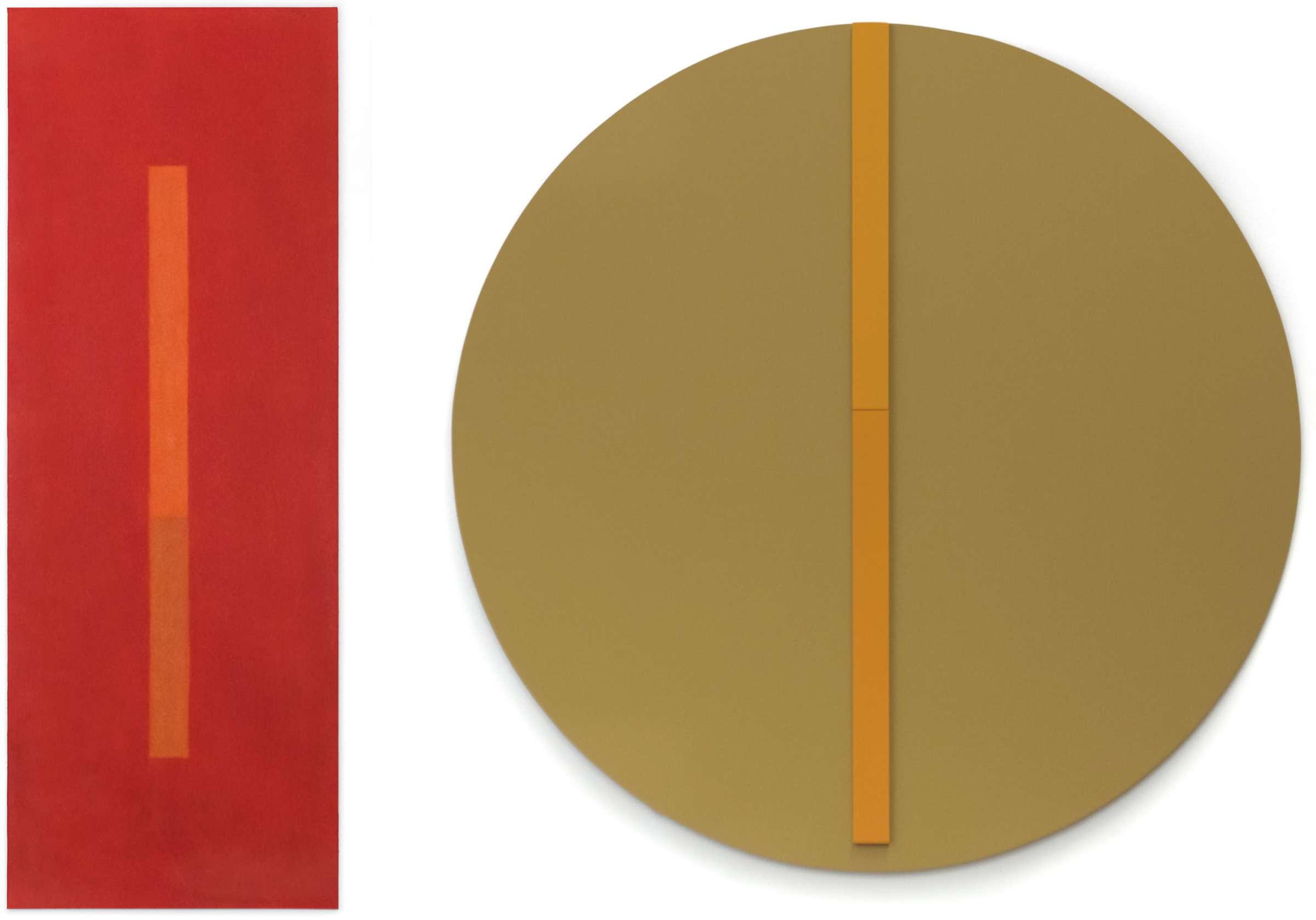

The third kind of drawings were those that were made after the sculptures had been constructed and relate to the finished sculptures compositionally. Sometimes the dimensions of the works on paper reflect those of the sculptures, for example as in the abstract, wall-dependent, sculptures constructed during the third distinct work period begun in March 2011. The drawings were treated differently than the sculptures. As a result, were seen by me as stand-alone works on their own. The drawings created a different dialogue with the viewer than that with the sculptures because of the materials used (charcoal and pastel powder versus copper and tin) in their completion as well as with their differences, normally, in scale. These drawings allowed for the quality of line to be different without wandering far from the original composition. Variations were made to reveal other options in terms of colour and line. It is important to realize that these drawings were entities unto themselves that could also usher in other possibilities and should not be seen as exact blueprints of the finished sculptures.

With the works on paper, I am not interested in supressing evidence of their making by my hands or by some special tool. The reading of the work is a combination of the composition and how the drawing is developed. In many of the drawings, there is a juxtaposition of ridged edges that are defined by the geometric shapes with ephemeral-coloured surfaces that at times fluctuate. There is a liaison that exists between the uneven distribution of coloured pastel powder and the geometric composition. The viewer is expected to go beyond the formal composition to emotionally enter and absorb the work.

The drawings for the second period began in 1987, with my first large free-standing sculpture titled, “Images”, May-June 1987, ushered in my use of symbols and metaphors to create a short narrative. That approach to recording my ideas on paper was sidelined for a period while I worked directly constructing small sculptures as models that were seen as studies for possibly larger versions. Very few drawings were made during the construction of the “Portrait of the Artist” series. Often notes were written instead of working drawings. More times than not during this conceptual figurative period, I started to construct work based just on an idea that I had. For the “Icarus” series I made 7 bronze studies with only written notations on the work.

The third working period that ushered in my reinvestigation of abstraction, in March 2011, began with the copper and tin wall constructions. There were fewer working drawings in this initial period of my return to abstraction as the work was constructed and developed as it was being worked on. However, I did make a number of small wall sculptures as studies that bore a similarity to the final version. It was not until 2013 that I started making drawings again in quantity. The drawings allowed me to explore other ways of depicting and developing the initial idea. Drawings for this body of work were made using charcoal and graphite. Once again, the drawings were seen by me as stand-alone works as the paper offered one type of surface to express my ideas that was different from the other physical surfaces that I was exploring and working with in the construction of my sculptures. With these drawings, I began treating and approaching the paper as if it was any other material I was exploring. The paper surfaces could be altered using a variety of sandpapers or scrubbed with a wire brush or simply made coarse using a variety of tools to create an irregular, textured surface that I used in the construction of my sculptures. The charcoal or graphite was then worked into the paper to develop the drawing.

From 2012 onward, I continuously made small 7” h X 5” w idea drawings as they emerged in my mind while working on the construction of my sculptures. When those ideas came up while working on a sculpture, I would make notations of my thoughts with the idea of re-examining those ideas another day. For many years, I created between 100-150 such drawings. From this collection of drawings, I might construct possibly 5% by years end. The completed sculptures invariably suggested other sculptures to pursue.

With 2015 I began combining charcoal and pastel powder to create rich coloured surfaces as in Zig No.1, November 2015. With “Trace No.1 (variation No.2, 2017). The lyrical charcoal lines seem at times to disappear against the ground as they move vertically in tandem with the contained straight lines. The straight linear components and lyrical lines compliment and punctuate the flat ground.

Making a sculpture often takes a great deal of time from beginning to end. As a result, my body is frequently in one place while my mind is motoring along thinking of other things that come up as I am working on the sculpture at hand.

When these ideas come up, I quickly record my thoughts as my memory is such that I will likely forget them while trying to complete the sculpture that I am working on. Consequently, there is always a small pad in the studio to record those ideas that may or may not be followed up on. As in the past, the idea drawings are put into envelopes that are dated as they correlate to the date on the drawings. Eventually I would look at those drawings. Sometimes weeks or months will pass before I look at those idea drawings again. Enough time will have passed by then that my head is likely to be in another space. As a result, I will see those ideas with fresh eyes. If they are worthwhile pursuing, I will make them. Not all ideas are worth pursuing further but they are relevant in keeping the imagination in motion and are a good record of my thoughts.

From 2017 onward, I have continued to make many pastel powder-coloured studies of my proposed aluminum wall sculptures. These drawings offered the opportunity to make colour studies of the compositions I was considering constructing or in some cases had constructed already. In the latter case, they were seen as further options. Often these drawings are the same size as the final wall construction. The paper surface offered a different visual response than the powder- coated aluminum sculptures, which I liked a great deal.

My drawings have always been about the work at hand in the studio. The drawings have been studies for work that will be realized or statements about the completed work or they have been about other ways of examining a finished work.

The drawings are a record not only of my thoughts, as in the idea drawings, that have come before the finished work, they are also a record of what I have made. Making a drawing of an idea often takes a long period of time between the start and the final realization of the idea. A great deal of time can be spent considering the many options a composition can offer. Even as the work progresses, thoughts on its conclusion are constantly being re-evaluated. I always leave room for the element of chance to introduce something not necessarily previously considered. Allowing chance to alter the direction that a work will finally take is essential to discovering new and unexpected aspects that were not previously considered. Surprises that unfold magically take the work occasionally in different directions than what was initially imagined.

I cannot say that I have created a brand when it comes to my works on paper. I have a history of constantly changing how I present the imagery of my works on paper.

There has not been that kind of continuous repetition that might lead to identifying who made the work. It is not about the continuity of a drawing approach that interests me but rather that I find a way to represent the next body of work in a way that reflects the three-dimensional work.

The work produced since 2011, with my re-examination of abstraction, has not been about something regarding daily life as it was during my second defined/distinct work period but rather that it grows out of my imagination. That re-examination of abstractions has been the focus of my ongoing interest in line and how the use of line impacts on the reading of a work be it two-dimensional or three-dimensional. It can be as simple as a single line moving across a large open field or as complex as a group of lines defining an architectural space.

The works on paper are the two-dimensional representation of my ideas. Though this body of work relates to the three-dimensional work it is nonetheless independent of it. They are stand-alone work. The translation of the ideas on paper offers the viewer a different way of seeing and understanding an idea and composition. The results direct how the three-dimensional might unfold in spite of the great differences in materials and processes.

The approach to presenting an image, at times, has developed using a number of different drawing materials, i.e. charcoal and pastel powder. At other times the works on paper have been constructed with the initial outline of the composition defined using a template. The template allows for the exact replication of the composition when the work is made with a series in mind.

There have been times when the exterior perimeter of the work on paper has been shaped much like the finished sculpture. At other times the final image has been developed across a traditional ground i.e., rectangular, or square format.

My drawings in the end offer a different way of looking and appreciating the finished sculptures.

The different series of wall sculptures that followed, once again, saw line being supported by varying regular and irregular grounds. The linear elements continued to explore new ways of experiencing how line could interact with the grounds in the completion of a defined composition.

The ensuing series “Journey”,” Linear Composition”, “Nazca, “Fusion” and “Crossings” continued to explore the visual impact of strong chromatic colours. Within the different series line continued to have a prominent role in tandem with the dominant ground.

It was not until the “Crossings Rising” series that line, once again, shed the earlier supportive and at times dominating grounds. The linear components, much like the earlier “Wrap” series, strongly defined the composition and truly became the subject. With the new “Crossings Rising” series came a shift in how line was used and presented.

Where the linear elements of the “Wrap” series physically reached into the viewers physical space the new series has the linear elements hugging flatly to the wall. The layering of the lyrical and straight lines is organized in such a way as to create opposing diagonal movements.